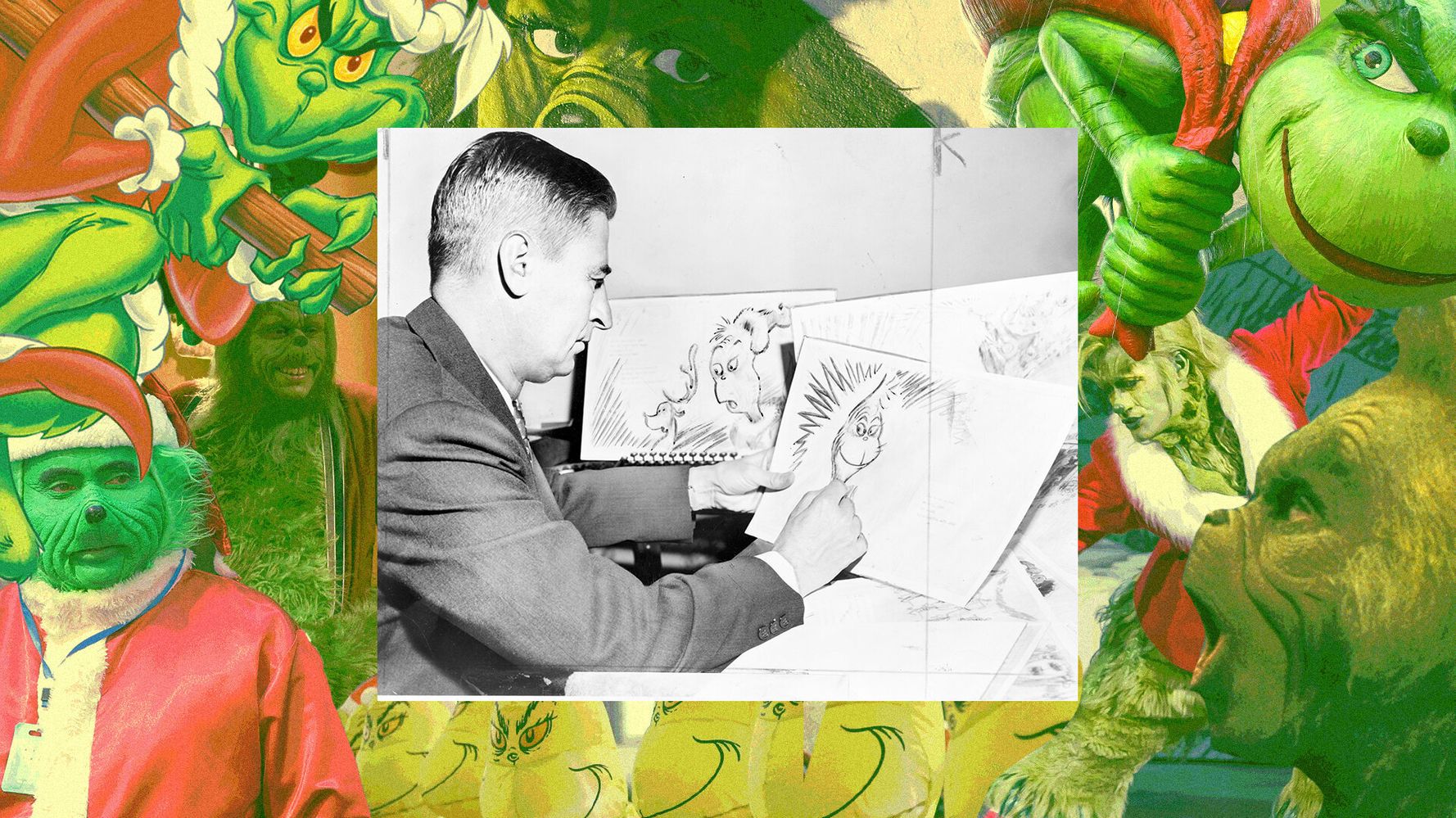

On the day after Christmas in 1956, Ted Geisel looked in the mirror and didn’t like what he saw. The 53 years of lines and weather on his face were not, he thought, dignified. They seemed corroded, maybe even corrupt.

It was not that he disliked what he did. Or at least, most of it. He wrote picture books for children, and The New York Times and The New Yorker approved. Sales were sufficient to justify a home in the beachfront San Diego district of La Jolla. Ted liked the sand. He liked the surf. He liked being asked to serve on the board of the San Diego Fine Arts Museum. Most of all, he liked working with his wife, unofficial editor and creative partner of 30 years, Helen. But his royalties were not quite sufficient to support the medical bills for Helen’s mysterious illness.

Two years ago, she had retired early from a party citing severe pain in her feet ― something more than the ordinary trouble with high heels. Within hours she was paralyzed from the neck down, eventually losing even her ability to speak. The doctors believed Helen’s immune system had gone haywire and attacked her neurological system. It was as sound a diagnosis as any, but it hadn’t led to a particular treatment, and Helen’s recovery had been arduous. Once she was out of the iron lung, Ted spent hours reading letters and literature to her, wheeling her to windows for a good view or whizzing down hospital corridors for thrills. By Christmas 1956 she was walking and talking, complaining only of a persistent pain in her feet that felt, she said, as if she were wearing shoes a few sizes too small.

Ted took on some ad work to keep the bills from getting the best of him, drawing billboard pictures for Standard Oil. The work was much easier than concocting narratives and language lessons for tots, but it left him feeling dry, denuded, ready for a drink.

And Ted loved a good cocktail; his excess with alcohol extended back to his college days. His smoking habit, too, had a tendency to accelerate into chain territory when he was working hardest. These chemical indulgences didn’t seem to detract from his work. If anything, he was producing the best stuff of his career. But it was taking a toll on his psyche. His passion was becoming a commodity. He was becoming a commodity. His publisher, Random House, had taken to releasing his books in late autumn, timed for the Christmas market. Was he teaching kids to read, or just giving parents something to buy?

The whole enterprise was starting to feel phony. Were his books really any different from his side hustle in highway billboards? Was Christmas itself about anything more than money?

A year and a half earlier, he’d dashed off a 32-line illustrated poem for the magazine Redbook, a little morality tale in which a greasy con man convinces a nice, regular guy to buy a piece of string by persuading him it was better than the sun itself. When Ted looked in the mirror on that December morning, he saw the villain of his own creation: the Grinch.

The Grinchy Paradox

By the time Ted and Helen released a full-fledged book on the Grinch in December 1957, his character had transformed from the charlatan of the Redbook cartoon into a bona fide hero.

“I’m really on the Grinch’s side,” Ted told journalist Sally Hammond in 1969. “The Grinch is against the commercialization of Christmas, even though he’s a mean old so-and-so. … I was cheering for this guy.”

This account of how the Grinch came to be is mostly compiled from three biographies ― Dartmouth English professor Donald E. Pease’s “Theodore Seuss Geisel,” the intimate portrait “Dr. Seuss and Mr. Geisel” by family friends Judith and Neil Morgan, and Brian Jay Jones’ “Becoming Dr. Seuss.” Other notes are gleaned from Richard H. Minear’s analysis of Geisel’s early political cartoons, “Dr. Seuss Goes to War.”

It’s difficult for any parent of young children not to identify at least a little with some of the Grinch’s gripes. “All the Who girls and boys would wake bright and early. They’d rush for their toys! And then! Oh, the noise! Oh, the Noise! Noise! Noise! Noise!” It’s a wonderful thing to see a child entranced by a toy, but it can also be a bit much.

Though the parallels between the Grinch and Charles Dickens’ anti-Christmas miser Ebeneezer Scrooge are unmistakable, the characters experience very different final acts. Scrooge undergoes an epiphanic reform and decides to reject money in favor of love and family. In the Seuss fable, it is not the Grinch who changes but the world. When the Whos down in Whoville wake up and see their toys are gone, they don’t “all cry ‘Boo-hoo!’” as predicted ― they go outside and hold hands and sing songs anyway. This spirit of community warms the Grinch’s heart and persuades him to give back the toys he has stolen.

The Grinch can afford to be magnanimous since the toys have become superfluous. The Grinch wins.

The green prophet of anti-consumerism is himself an enduring Christmas commodity, his legacy secured not by teachers and churches but by television and, yes, toys.

There is an inescapable irony surrounding the Grinch and his status as an American Christmas staple. The green prophet of anti-consumerism is himself an enduring Christmas commodity, his legacy secured not by teachers and churches but by television and, yes, toys.

Hollywood has enhanced this Grinchy paradox, but the tension goes all the way back to the book’s beginnings. The major Seuss production in 1957 wasn’t the Grinch, but “The Cat in the Hat,” a book that for 11 months of every subsequent year remains the most iconic offering from the Seuss catalog.

Ted dealt with his post-Christmas malaise by working on a book that was extremely wholesome and totally un-Christmasy. Textbook publisher Houghton Mifflin wanted to jump the market for elementary school reading primers. Educators were taking the laggard U.S. literacy rate seriously ― it was a question of national pride during the Cold War ― and big pedagogical thinkers of the day had noticed that kids actually seemed to like the Seuss books. The early stages of reading are difficult for children, and the books designed for the youngest readers were extremely dull, filled with bland characters like Dick and Jane who don’t really do anything more than “See Spot run.” If Dr. Seuss could make reading exciting, even silly, then educators would have a better shot at setting kids up for success.

Ted and Helen had been on a roll. Starting in 1954, they’d been producing nonstop classics ― “Horton Hears a Who!,” the A-B-C book “On Beyond Zebra!” and the fantasy romp “If I Ran the Circus” ― adored by critics, teachers and parents alike. But they operated at a relatively high level for children’s literature. “Horton” swelled to nearly 70 pages, most of them filled with dense blocks of text peppered with words that most children didn’t know and certainly couldn’t read on their own.

“The Cat in the Hat” would be different. Houghton Mifflin asked Dr. Seuss to tell this tale with no more than 250 simple words and to make it easy for children to identify the specific objects described, keeping adjectives to a minimum and eliminating the zany nonsense words that were part of the Seuss brand.

That was tricky enough, but the hard part was making it fun. “If you drop the charm,” Ted told the Boston Herald American about “The Cat in the Hat,” “you have a dictionary.” The stroke of genius was the Cat himself ― a debonair rogue who swashbuckles through a family home pulling stunts and breaking rules. Reading, the book suggested, was edgy and cool ― maybe even as cool as a talking cat balancing on a ball while holding a cake.

Houghton Mifflin released “The Cat in the Hat” in March 1957, hoping to generate enough buzz to persuade school systems to pick it up for the fall curriculum. The publisher was so intent on tackling the institutional market that it let Random House ― a competitor who had handled all of the previous Seuss material ― collect whatever it wanted from sales to retail bookstores.

That proved to be a spectacularly bad bet. Schools didn’t bite. Dick and Jane would maintain their hegemony over educational officialdom for decades to come. But “The Cat in the Hat” was a retail smash. “Horton Hatches the Egg,” the first true masterpiece in the Seuss canon, had sold fewer than 6,000 copies when it was released in 1940. “The Cat in the Hat” quickly sold 250,000. Dr. Seuss went from a name that book critics knew to a name that everyone knew.

“The Cat in the Hat” changed children’s publishing, demonstrating that selling directly to families could be a bigger and more influential business than selling to school systems. Dr. Seuss may well have been improving American literacy, but what Ted and Helen had created was also unmistakably a retail commodity. The Cat was famous the way movie stars were famous, the product not of public education but of consumer capitalism.

The Grinch was a commercial slam-dunk, the biggest thing to happen to Christmas since ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ stormed the Billboard charts in 1949.

Random House, of course, wanted another Seuss book in time for Christmas 1957. After doing their good deed for children’s literacy, Ted and Helen were happy to comply. What they came up with was an anti-Cat in the Hat. Where the Cat flouted house rules, reveling in cakes and kites and cleaning up only to keep from getting caught, the Grinch was a relentless stickler, possessed by the Puritan asceticism of a cave-dwelling monk. Visually the two characters invite comparison ― nix the whiskers and the hat and swap out the Cat’s rounded gloves for pointed fingers, and you have the Grinch. Placed side-by-side, the covers of the two books look like a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde cartoon.

With the Seussian imagination freed from Houghton Mifflin’s pedagogical constraints, Ted cranked out nearly the entire narrative for “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” in a few short weeks. But the ending bedeviled him for months. Like all of the best Seuss books, the Grinch carries a strong moral current, and Ted worried about laying it on too thick.

“The message of the book is we are merchandising Christmas too much,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1982. “But I found I could take it into very sloppy morality at the end. I tried Old Testamenty things, New Testamenty things. It was appalling how gooey I was getting.”

Helen’s chief concerns were with the art, according to biographer Brian Jay Jones. “You’ve got the Papa Who too big,” she told Ted after one attempted finale. “Now he looks like a bug.”

“Well they are bugs,” Ted argued.

“They are not bugs. The Whos are just small people.”

Helen’s vision would win out in the TV special a decade later, but the Whos in the book do resemble talking insects, the descendants of Ted’s early ad contracts with Standard Oil’s premier bug spray. Her influence over the book is comprehensive ― the narrator wonders if the Grinch’s shoes are a few sizes too small before concluding that, actually, it’s his heart that is undersized.

After wrestling over different religious themes for the ending, Ted and Helen decided to cut out the Bible altogether and let the Grinch settle down to dinner with the Whos, slicing the roast beast as everyone lives happily ever after.

Riding the Cat’s coattails, the Grinch was a commercial slam-dunk, the biggest thing to happen to Christmas since “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” stormed the Billboard charts in 1949. But there were a lot of books that sold well for Christmas in 1957 ― that’s what books do this time of year.

No, the Grinch’s bid for immortality came not on the printed page but in Hollywood. And it was Hollywood that would transform Dr. Seuss from a popular children’s author into an American icon.

The Grinch Goes To Hollywood

Chuck Jones was an animation legend ― the brains behind Warner Bros. powerhouses Bugs Bunny, Marvin the Martian, Wile E. Coyote and the Road Runner.

None of that mattered much to Ted Geisel. Old friends are the hardest to impress, and once upon a time, Ted and Chuck had worked side-by-side under Hollywood super-director Frank Capra in President Franklin Roosevelt’s War Department. They’d produced educational cartoons for semi-literate enlisted men explaining army life, combat duties and the moral substance of the conflict with Germany and Japan, using a goofball character of Capra’s named Private Snafu. Nothing ever went right for Private Snafu ― so long as soldiers did the opposite of whatever he did, they’d come out OK.

Ted had loved the work. “I must confess I learned more about writing children’s books when I worked in Hollywood than anywhere else,” he told The Saturday Evening Post in 1965. “In films, everything is based on coordination between pictures and words.”

And Ted and Helen had been flawlessly coordinating pictures and words since the Grinch, producing classic after classic: “Yertle the Turtle,” “One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish,” “Green Eggs and Ham” and “Hop on Pop.” So in 1966, Jones made the two-hour trek from Hollywood to La Jolla, hoping to talk the world’s most popular children’s author into bringing his creations to television.

But Ted’s most recent memories of Hollywood were bitter. In 1953, he’d been the primary creative force behind “The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T” ― an eruption of surrealist brilliance that nevertheless left movie audiences and the industry cold. Ted had limped back home to channel his frustrations into “Horton Hears a Who,” the tale of a gentle elephant whose efforts at kindness are thwarted by a cruel and ignorant jungle establishment. Book critics cheered “Horton,” and Ted swore off the movie business forever.

Or so he thought. Jones was envisioning something much grander than the typical cartoon special. Despite his impressive résumé, Jones desperately needed a hit. Warner Bros. had canned him after 30 years for moonlighting on a Judy Garland feature in violation of his exclusive contract. MGM had given him a job asking him to breathe some life into the dusty Tom-and-Jerry franchise, but Jones could see he was circling the drain with has-been characters. His future in Hollywood depended on his ability to come up with something bold and new, and he was willing to go for broke to make it happen.

The result was a sensation, superior to the book and quite possibly the best thing Dr. Seuss ever did. Everything in pop culture about the Grinch derives from the TV special.

His pitch to Ted and Helen was simple. With the Seuss brand, Jones could raise whatever money they needed to make the project shine. They’d bring in the best specialists in the business for backgrounds and illustrations. They’d hire an orchestra to cut original songs, get a professional choral unit to sing the lyrics and contract with a real star for voices and narration.

But the not-so-secret weapon was Dr. Seuss. The biggest problem with cheap cartoon features wasn’t the visuals but the scripts. Most big movie studios didn’t even respect the intelligence of an adult audience. When it came to writing for children, almost anything that walked and talked was considered acceptable. Tom and Jerry didn’t even talk.

The Seuss books worked because parents liked them, and parents liked them because the stories had real characters and substantive plots. They’d have to pad the narrative a bit with songs and montages, but Jones wanted to keep Ted’s original words and tone. They didn’t need a bunch of new screenwriters ― they already had their man.

Helen was sold, and so Ted soon followed suit. The question was which book to film. Jones had initially written to Ted with an illustration of the Cat in the Hat to prove he could mimic Ted’s drawing style. But the mid-1960s were the heyday of animated Christmas specials. The claymation “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” had been a smash for NBC in December 1964. One year later, CBS had scored a surprise hit with “A Charlie Brown Christmas.” “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” conveniently combined key themes from both ― the Santa myth, dissatisfaction with commercialization ― without any overt appeals to religion. If they got started right away, the project would arrive just in time for the holidays.

Jones got to work scrounging up corporate sponsors for the big anti-consumerism holiday special. Most companies were understandably reluctant, but he eventually persuaded the Foundation for Commercial Banks to pony up enough cash to support the grandiose production values he’d envisioned. According to Jones, “How the Grinch Stole Christmas!” ultimately used five times the typical number of drawings in an animated feature, ensuring that the movements of the characters felt natural and giving the entire show a glossy sheen. Riding the Christmas special wave, Jones then convinced CBS to pay $315,000 for the Grinch, roughly four times what it had paid for Charlie Brown a year earlier.

The result was a sensation, superior to the book and quite possibly the best thing Dr. Seuss ever did. Everything in pop culture about the Grinch derives from the TV special. Book-Grinch is a black outline on a white background. He turned green on TV in 1966 and has remained so in the public imagination ever since. The songs are by turns gorgeous and menacing. Don’t bother to make sense of the lyrics to “Welcome Christmas.” Much of it is nonsense words, or “Seussian Latin” as Jones described it, with hypnotic phrases like “Fahoo fores, dahoo dores” that mean nothing and feel wonderful. The show’s narrator, Boris Karloff, would notch a Grammy for the vocal performance “You’re a Mean One, Mr. Grinch” ― even though he hadn’t sung a note. A singer named Thurl Ravenscroft had taken care of the vocals, but the svelte opening credits didn’t name the musicians and so the Grammys honored the wrong man.

The broader role that Jones carved out for the Grinch’s dog, Max, enriched the moral complexity of the TV version. Though he barely registers a cameo in the book, Max is the most important supporting character here, “a witness and a victim,” as Ted put it, of the Grinch’s worst behavior. The Grinch remains the hero of the story, but his cruelty toward the character closest to him provides him with a more interesting moral arc ― the decency of the Whos really does make him a kinder creature, even if he’s been right all along. Max even gets to sit at the table and share in the roast beast.

The Grinch, in short, became more like Ted himself.

Why We Still Love The Grinch 60 Years Later

In 1964, after nearly 40 years with Helen, the 60-year-old Ted began a secret affair with 43-year-old Audrey Dimond ― the wife of Ted’s best friend, Grey Dimond, a prominent cardiopulmonary specialist in San Diego. The two couples were close, double-dating all over town and throwing parties together.

No one in Helen’s inner circle knew if she ever discovered Ted’s infidelity. But her final note, cited by Judith and Neil Morgan in “Dr. Seuss and Mr. Geisel,” written before an intentional overdose of barbiturates in 1967, makes clear her despair. “What has happened to us? I don’t know. … I love you so much. … I am too old and enmeshed in everything you do and are that I cannot conceive of life without you.”

Ted and Audrey married in 1968. Audrey’s ex-husband remarried not long after and continued an illustrious career, ultimately writing 16 books himself. Audrey’s children embraced Ted as a “wonderful man” and delighted in having him in the family. But the Seuss magic died with Helen. Random House co-founder Bennett Cerf mourned Helen as “a worker,” “a creator” and “the most unselfish person we’ve ever known.” Without his lifelong manager and creative partner, Ted just didn’t have the same spark. He continued to publish under the Dr. Seuss moniker until his death in 1991, riding the brand to the occasional fluke best-seller, but he only mustered one more bona-fide classic: 1971’s scathing assault on big business, “The Lorax,” which, unlike previous classics, sold poorly.

Ted became the beloved manager of a deteriorating brand. He did more TV and the Grinch decayed into parody. Both “Halloween Is Grinch Night” (1977) and “The Grinch Grinches the Cat in the Hat” (1982) won Emmys, but both TV specials were devoid of substance, even annoying, lacking the moral complexity of the Seuss Christmas fable. The Grinch became another boring bad guy out to hurt the good guys for no reason. In 2000, Ron Howard teamed up with Jim Carrey for a live-action version that proved an insult to cinema, the Seuss legacy and family itself. The magic formula for the Grinch is in the tension between commerce and community. When commerce wins out, the result is repulsive.

2020 has been a spectacularly bad year. Millions of us have lost loved ones to disease and still more to conspiracy theorizing and amorphous anger. Our political culture, from the president’s bluster to the micro-disputes that bloom on social media, has nurtured the nastiest elements in our country and ourselves. Most of us won’t marry the wife of our best friend, but that bit of the Grinch that lives in us all has been encouraged to do his worst.

And that is precisely what makes the Grinch so compelling. We may not always overcome the cruelty within us, but we can if we so choose. Our communities are always capable of greater kindness than we imagine. It is never too late to come together, even when it seems like everything that matters has been taken from us.

That will be hard to do this year, when we are so isolated from one another and so many families are forced to celebrate over phone calls or FaceTime. And yet love is always all around. The Grinch is indeed a work of fantasy that the engines of consumer capitalism propelled to fame. But the story has endured for more than six decades because it is, in the deepest sense, true.

Fahoo fores, dahoo dores, welcome Christmas, Christmas Day.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter