CHICAGO – First it was a Toyota pickup.

Then a sky blue Lamborghini.

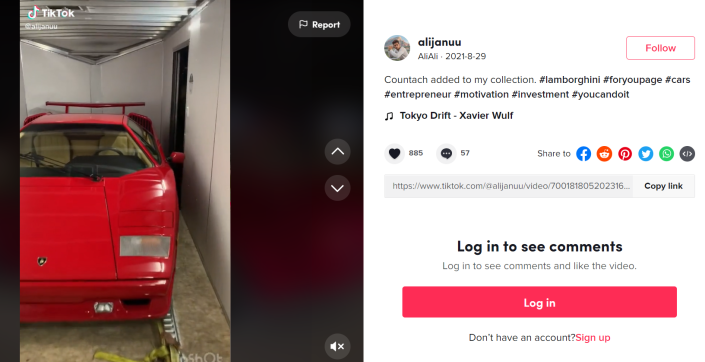

Then, at the end of August last year, Illinois resident Akbar Ali Syed posted a TikTok video of a red Lamborghini Countach being unloaded from a flatbed truck.

“Countach added to my collection,” Syed wrote in the caption, adding the tag “#entrepreneur.”

“Oil money?” a user asked.

No, Syed responded, “COVID money.”

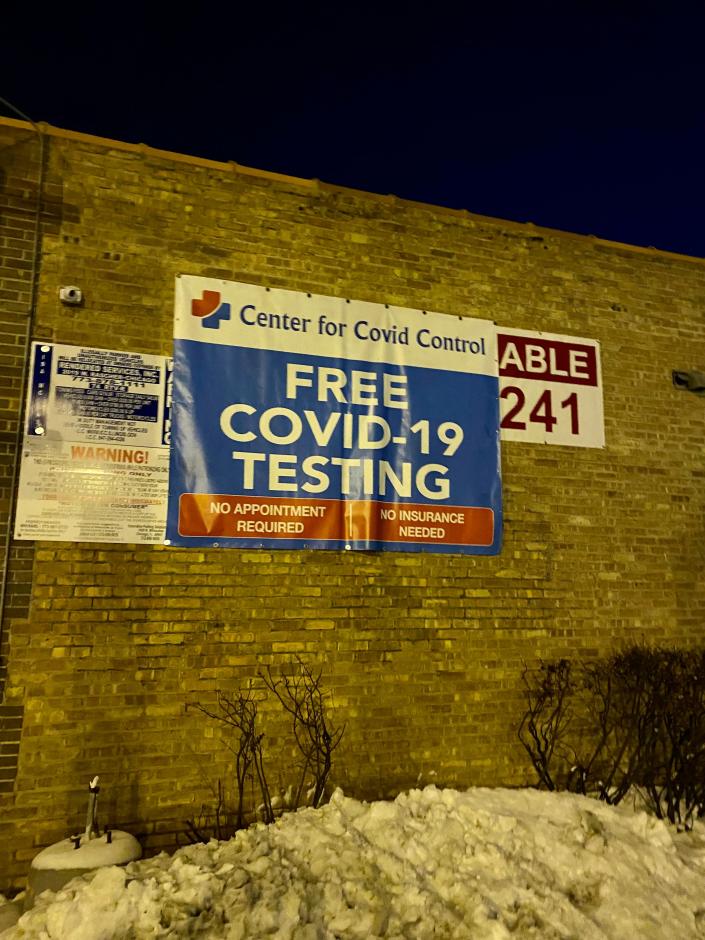

Questions swirl around more than the cars and Syed’s new $1.36 million mansion. The inquiries are focused on a nationwide chain of coronavirus testing sites known as the Center for COVID Control, under scrutiny by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, the Oregon Department of Justice and multiple state health departments.

Test takers at the company’s more than 300 locations across the USA have reported the sites to state and local authorities, saying they received delayed test results, no results or multiple conflicting results, among other concerns. The company has the Better Business Bureau’s lowest customer review rating, and social media pages and Google reviews for the sites are filled with complaints.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services documented numerous “deficiencies” at the company’s main lab, Doctors Clinical Lab, which has been reimbursed more than $124 million from the federal government’s COVID-19 uninsured program, according to public data. Private health insurers also paid the lab.

At its peak, the company said it collected more than 80,000 tests per day. The federal government reimbursed some labs at a rate of $100 per PCR test. It was not immediately clear how much the lab billed private insurance companies.

Though much about the company remains unclear, one thing is certain: Longtime entrepreneurs Syed, 35, and his wife, Aleya Siyaj, 29, are behind the operation. And – until recent days – they’ve been unabashed on social media about their growing wealth.

What is the Center for COVID Control, and how did it come to be?

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States has struggled to provide quick, easy and accurate coronavirus testing. Nearly two years into the U.S. outbreak, the Biden administration is still rolling out plans for insurance companies to cover the cost of over-the-counter tests and introducing a website where Americans can order free tests.

The Illinois-based Center for COVID Control cropped up in 2020 to fill a hole in the market. Siyaj, whom the company refers to as the “CEO and founder,” registered the company in December that year, state records show.

“CCC was founded to meet a critical market need to establish testing centers where COVID tests could be provided to patients rapidly and safely to minimize delay, and let people get on with their daily activities,” Siyaj said in a statement Thursday. A company spokesperson did not respond to requests for comment Friday and Saturday.

The Center for COVID Control’s principal and mailing address is in Rolling Meadows, Illinois – a one-story commercial office building about 15 miles northwest of O’Hare International Airport.

The company says it “primarily uses” Doctors Clinical Lab as a clinical testing vendor partner. According to public records, the lab is registered with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration at the same Rolling Meadows address as the Center for COVID Control.

A federal agency under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is investigating the lab for several alleged instances of misconduct. Employees work out of an office at the address and answer calls for both the lab and Center for COVID Control, the agency said in public filings. Syed and Siyaj work out of that office as well.

A photo of the Center for COVID Control call center obtained by USA TODAY shows a monitor at the front of the room listing caller wait times for both “customer service” and the “test lab.” A USA TODAY reporter called Doctors Clinical Lab last week and was directed to a recorded message for Center for COVID Control.

As Center for COVID Control testing sites cropped up throughout the USA, Syed documented the company’s journey on his public social media pages.

In one since-deleted Facebook video posted July 29, 2021, Syed, under the Facebook name “Akbar Syed Raza,” showed viewers around what he called a Center for COVID Control office. In the video, Syed summoned a man named “Neal.” Prompted by Syed, the man informed viewers he started working for the company in March.

“So what’s your annual salary at right now?” Syed asked.

“1.4-5 mil,” the man responded.

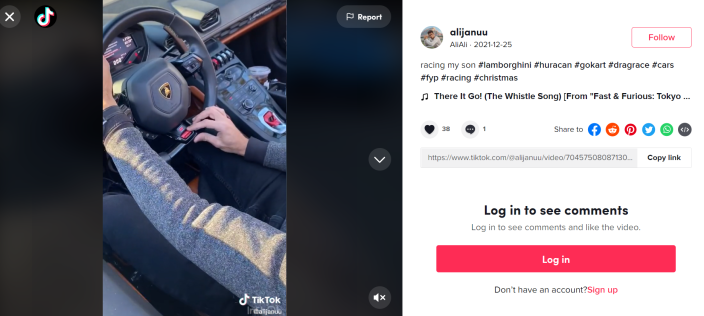

On his public TikTok account, which was taken down Thursday, Syed often shared photos and videos of high-end cars. Syed’s nephew, an employee of the company, chronicled the family’s growing car collection on his public YouTube channel.

In a post Aug. 15, Syed shared an image of what appears to be a baby blue Lamborghini on stage at an auction, and he wrote, “bidding on one of my dream car.” Ten days later, Syed shared a video of a blue Lamborghini being unloaded from a truck in front of his home. “Dilevery Day!” he wrote.

Four days later, on Aug. 29, he shared a video of a red Lamborghini Countach being unloaded from a truck.

In a Sept. 5 video, two vehicles raced down a street. “Huracan Vs R8 #lamborghini #audi #r8 #hurcan,” Syed wrote. Later that month, he shared a video of himself approaching a home, preparing to surprise his wife. He wrote, “wife wanted a non 5g phone.”

The Center for COVID Control seemed to be going well for Siyaj and Syed through early fall. It was not the couple’s first business venture.

Before COVID testing: Wedding videos, donuts and ax throwing

In 2013, Syed ran a wedding photo and video company, according to former customers and archived pages of the business’s website.

In the past five years, Siyaj, his wife, has launched at least six businesses, according to Illinois public records.

Siyaj is listed as the owner of O’s Donuts & Cafe, which was incorporated in 2017 and involuntarily dissolved in November 2020, according to Illinois records. The company was licensed in Michigan from 2018 to 2020, according to state records.

Next came ax throwing: In early 2019, Siyaj established Axe Range, then in 2020, Axe Lounge, which was involuntarily dissolved the following year.

From 2020 to 2021, Siyaj established Aenaz, Lom Investments and Testing Solutions. An Illinois resident listed as the agent for all three businesses is listed as the agent for the Center for COVID Control.

‘Just enter ‘COVID test near me’ in the Google search bar’

The Center for COVID Control began experiencing trouble at the end of 2021, as the omicron variant of the coronavirus arrived in the USA. Cases surged amid the holiday season, and Americans frantically flocked to testing sites.

“Just enter ‘COVID test near me’ in the Google search bar and you can find a number of different locations nearby where you can get tested,” President Joe Biden said in an address to the nation in late December.

Tens of thousands of Americans did as Biden said. Many stumbled upon listings for Center for COVID Control sites and, with no appointments needed, hopped in line for tests. Business for the company increased, but to such a degree that testing sites became overwhelmed, revealing cracks in the delicate system.

Complaints emerged on the company’s social media pages and on site-specific Google reviews at the end of 2021. Rumors about the sites swirled through Chicago, and one citizen journalist even launched his own investigation into the company.

Siyaj and Syed continued to share their luxurious lifestyle on social media.

In November, Siyaj became the owner of a $1.36 million home in St. Charles, Illinois, according to Kane County records. A Zillow listing for the property shows a 3.65-acre lot on a private road with a gated entry, three-car garage, circular front driveway, fountain, white pillars, iron double doors, crystal chandeliers and a curved floating staircase.

A video posted Dec. 10 to the YouTube channel run by Syed’s nephew features the “unveiling” of a 2018 Ford GT. An identical 2018 Ford GT was sold for $985,000 on Dec. 3, according to Bring a Trailer Auctions.

Two videos posted to the YouTube channel Dec. 31 and Jan. 1 show the 2018 Ford GT sitting in the driveway of the St. Charles home. In the first, the lyrics “baby, I’m a gangster, too” play as the video rotates around the vehicle. The second video appears to show the car and home shot from above by a drone.

Syed shared videos on Facebook of him getting into a Ferrari Enzo.

On Dec. 22, 2021, a 2003 Ferrari Enzo – one of only 400 made by the extreme sports car builder – was auctioned off for $3.7 million to a person in Illinois, according to an online auction house. Supercars.net reported the sale set a world record as “the highest sale price achieved on an online car auction platform” and “the highest sale price achieved for a Ferrari Enzo at an online auction.”

USA TODAY first reported on the Center for COVID Control in early January after a reporter encountered one of the sites operating out of a generator-powered mobile storage unit in Chicago, where bags of tests sat piled in crates on the ground. Six days later, the company ordered a one-week “pause” on the collection of tests.

“Over the last week, we have seen increased scrutiny by the media into the operations of our collection sites,” the company said in an internal memo to employees, obtained by USA TODAY. “This, coupled with various customer complaints, resulted in various state health departments and even Department of Justice taking a keen interest in our company.”

Though local, state and federal authorities have cautioned Americans for months against visiting “pop-up” testing sites, none mentioned the Center for COVID Control by name – even though a federal agency was aware of rampant mismanagement at the main laboratory as early as November.

‘Non-compliance’ and ‘deficiencies’ at Doctors Clinical Lab

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, said it conducted surveys at multiple Center for COVID Control testing sites and “the main laboratory” in November and December and found “non-compliance” with numerous standards, affecting more than 400,000 tests. The agency said Friday it was waiting for a response from the lab on the cited “deficiencies.”

An 81-page report found the lab was in “immediate jeopardy.” Among other concerns, the report found the lab did not ensure all personnel had appropriate training, did not have appropriate equipment, did not comply with state reporting requirements, did not obtain a required state lab license, did not maintain confidentiality of patient information, did not accurately identify patient samples submitted for PCR testing and did not document complaints and problems reported to the lab.

Over 11 days in November, the lab received more than 84,000 samples for PCR testing but performed and reported slightly more than 43,000 results, the report found. The lab director did not have enough staff to perform the testing within 72 hours after collection and did not have the proper freezers to correctly store the samples, according to the report.

Asked about the report, Center for COVID Control spokesperson Russ Keene said, “The audit is of DCL; CCC has no ability or power to publicly comment upon it.”

“As a key vendor/supplier, CCC has reviewed the report with DCL, and worked with DCL in constructing DCL’s 10-Day response and discussion of corrective actions of items identified in the audit,” Keene said.

The federal report suggests the businesses operate together. Doctors Clinical Lab and the Center for COVID Control are at the same address, and employees who work at the lab’s call center refer to themselves as Center for COVID Control employees, according to the report.

Christina Morales, 29, worked at the main office – what she called “headquarters” – from July through December in the data entry department, call center and receiving department. A pay stub obtained by USA TODAY was sent from the Center for COVID Control.

Morales told USA TODAY she was hired after a friend at a karaoke bar gave her the number for one of the company’s managers. The next day, she walked into the unlocked office building and began doing data entry.

“I literally just signed a direct deposit form and a tax form. I never signed a HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) agreement or anything like that,” Morales said. “It was a little scary.”

HIPAA establishes national standards to protect individuals’ medical records and other individually identifiable health information.

Morales said Syed and Siyaj worked out of the office, and Syed’s cars were often parked outside. No one in the office wore face masks or gloves, she said, except when inspectors visited. For several months, staff put biohazardous waste in regular trash bags and disposed of it in trash bins, she said.

Doctors Clinical Lab was initially operating out of the office space and eventually moved to a location in Chicago, Morales said. The lab was initially attached to the Center for COVID Control call center through a set of French doors, and, if the blinds weren’t closed, call center employees could see directly into it, she said. Lab employees were paid by the Center for COVID Control, Morales said.

“I worked very closely with the lab manager up until they moved,” Morales said. “The lab manager is very close with Akbar and Aleya.”

Within three weeks, Morales was supervising the data entry team, overseeing 30 people. The company had 40 to 60 testing sites processing about 1,200 tests a day, she said.

“I kind of kept my head down for a while because money really does talk, and they were paying really well,” she said. “It seemed that every week or every other week, we were opening up another three locations. That’s when I noticed my team started having issues keeping up and catching up.”

Morales said Center for COVID Control operations began to crumble in late October amid a backlog of tests, which arrived from in and out of state without any ice packs and were often left out in the warm office for days. USA TODAY reviewed a video taken inside the office showing plastic bags of tests in cardboard boxes on the ground alongside unopened boxes of tests.

“We were still instructed to process tests that were a week old,” Morales said.

By December, the office received about 12,000 tests a day, but there were only 34 people on the data entry team, she said. “We were behind because they didn’t hire enough people to accommodate for all of the locations,” she said. “Going from 65 locations to 300 in the span of a few months, how do you expect us to keep up?”

The call center received “hundreds” of calls, Morales said, and the lab was five to six days behind on processing tests. “We would tell them, ‘I’m sorry, your results came back inconclusive, you need to go and retest.’ Those were our instructions from the director of operations,” Morales said.

Morales said customers’ sensitive personal information was shared freely on various company WhatsApp groups, which automatically download images to cellphones. “My phone was just kind of getting flooded with personal information being sent by the location managers all the time,” she said.

Another staff member who worked at headquarters confirmed Morales’ account.

The Doctors Clinical Lab location in Rolling Meadows was reimbursed more than $113.7 million for testing and nearly $9 million for treatment through the COVID-19 Claims Reimbursement to Health Care Providers and Facilities for Testing, Treatment, and Vaccine Administration for the Uninsured Program, according to public data. A Chicago location was reimbursed nearly $1.4 million for testing and nearly $50,000 for treatment.

The American Rescue Plan Act, a federal coronavirus relief package, provided $4.8 billion to reimburse providers for testing the uninsured, and the Families First Coronavirus Response Act Relief Fund and the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act each appropriated $1 billion.

Lack of training at test sites: ‘I didn’t know because nobody told me’

Employees of Center for COVID Control testing sites told USA TODAY they did not receive training on HIPAA compliance and were not provided with the equipment to ensure PCR tests stayed at stable temperatures.

Bravette Fleet said he started working at a testing site in Chicago in October. It was more than a month before the site secured a fridge for the test samples, he said.

“We would just sit them on a table and line them up and at the end of the day bag them up so that the driver can come pick them up,” he said.

Fleet said he finally realized he was supposed to place PCR samples in a fridge when he took it upon himself to read a manual left at the site.

“When I read through the book about the steps we were supposed to take, I realized we weren’t taking them,” Fleet said. “All of these things we weren’t doing that I didn’t know because nobody told me.”

Working out of an office space with no Wi-Fi, Fleet said, he often sent people their test results from his personal cellphones. One of Fleet’s former co-workers confirmed his account.

HOW DOES COVID-19 AFFECT ME? Don’t miss an update with the Coronavirus Watch newsletter

Heather Doty, a former microbiology lab analyst at Cardinal Health, said she started as a lab tech at a site in Hampshire, Illinois, on Dec. 6. “I had two hours and 45 minutes of training, and the next day was my first day alone,” Doty said.

Doty said her training consisted of observing site operations. She was not required to read any training material. She said she raised concerns on the first day and brought issues to the owner‘s attention.

“There’s certain things that as a lab tech, it’s common knowledge, common sense,” Doty said. “Having a moral consciousness, I was not OK with just letting things go.”

Devon Townsend, 18, said he has enjoyed working at a site in Wisconsin, though he’s aware of reports of issues at other locations. A freshman at UW Madison studying pre-med, Townsend said he started working at the site over winter break.

“There was no training required prior to opening,” he said, but employees received a written guide for review.

Before the site paused test collection, Townsend said, he worked from open to close each day. Speaking about the company broadly, he said, “It’s not like we’re out here trying to do anyone wrong, but people get all upset about a missed test result. We are trying our best, I promise.”

In an internal email obtained by USA TODAY that was sent to employees of a Chicago testing site, all staff members were asked to complete two training sessions – one from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and one on HIPAA compliance – and upload proof of their training certificates by Friday to a public Doctors Clinical Lab online form.

Each training session was expected to take approximately one hour, according to the email, which was sent and signed by the executive assistant of a car wash chain who worked as a site manager.

Asked about allegations made by former employees of the main office, as well as those at the testing sites, Keene said, “CCC fields such comments with great concern.”

“Such occurrences and practices are clearly not acceptable,” Keene said. The company’s “operational pause,” he said, was “intended to eliminate any deviations from company policies and return CCC to a trusted, national provider of accessible, accurate, affordable/no cost Covid-19 tests, offering peace of mind to thousands of patients who entrust us with this critical mission.”

The lab also faces scrutiny for its use of a trademarked logo. DCL Corp., a pigments supplier, sent a cease-and-desist letter to the company Monday for a trademark violation. A website for Doctors Clinical Lab, test forms and emails sent to test recipients feature DCL’s trademarked logo.

A Twitter account tied to the company’s website was “permanently suspended” Wednesday for “violating the Twitter Rules,” a Twitter spokesperson said.

Have more information about the Center for COVID Control? Email reporter Grace Hauck at [email protected].

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Center for COVID Control got millions, then failed patients nationwide