[ad_1]

Of the movies made during the pandemic thus far, “Malcolm & Marie” is probably the one with the highest profile. In September, Netflix paid an astounding $30 million to acquire the film, which debuted Friday in an apparent bid for awards-season recognition.

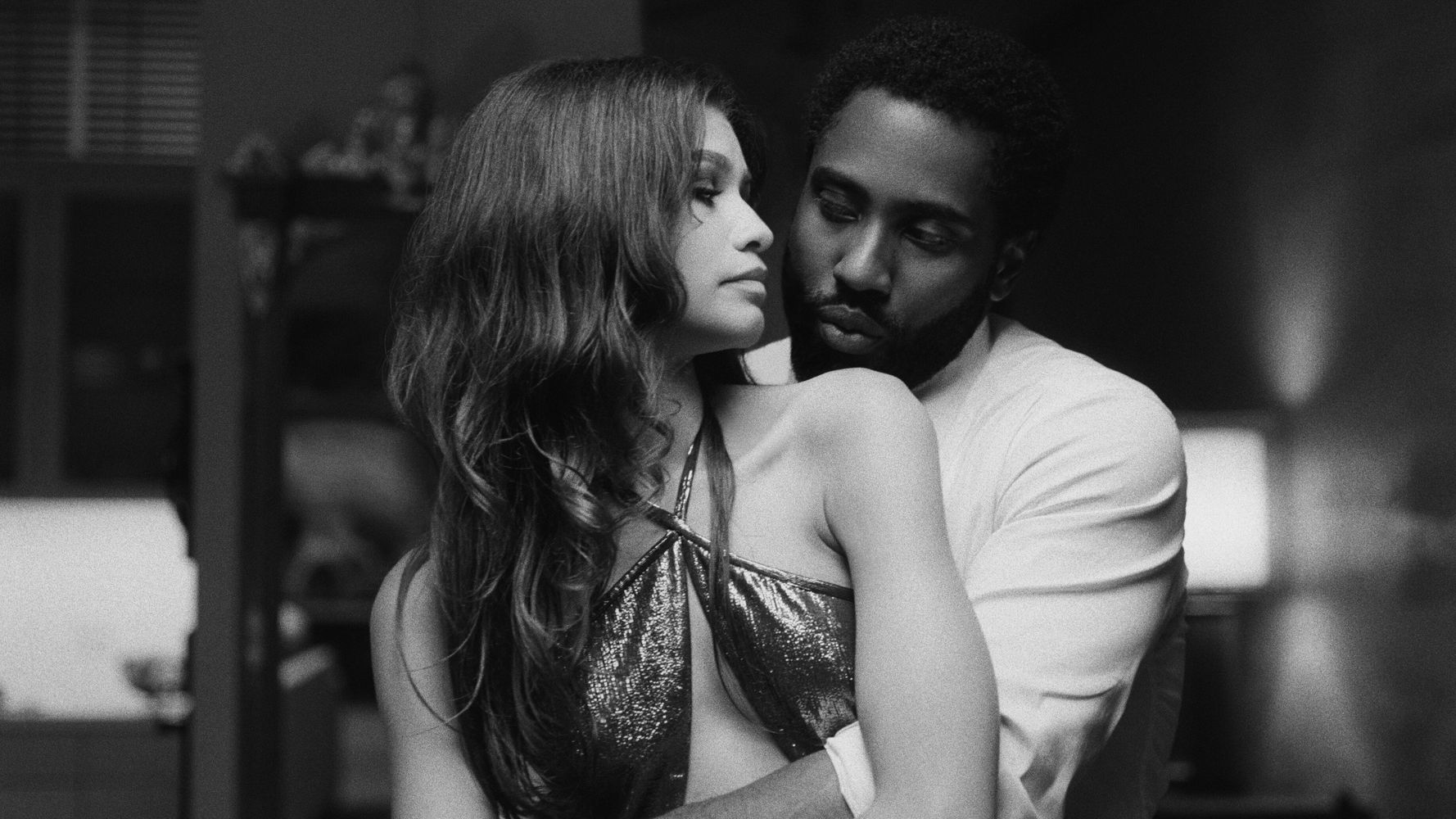

“Malcolm & “Marie” begins with its title couple arriving at their palatial California rental home. Malcolm (John David Washington) is a director whose new movie just had a rapturous premiere. He’s on cloud nine, reveling in the praise and mocking white sycophants’ performative fawning. Marie (Zendaya), meanwhile, is not so charmed. Despite having lifted details of Marie’s former drug addiction for his film, Malcolm forgot to thank her during a speech, inflaming a fundamental issue in their relationship. What follows is a long, stormy exchange about art, Hollywood and what partners owe each other.

“Euphoria” creator Sam Levinson wrote and directed “Malcolm & Marie” after Zendaya suggested they make a movie together as COVID-19 shut down most productions. Photographed in slick black and white, its debt to the hothouse tension of “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” is obvious.

“We spent like two weeks in a bubble before we started shooting,” Hungarian cinematographer Marcell Rév said. “We were quarantined in a property next to the location. It’s like rehearsing, but at the same time, we were trying to figure out how this looks and how we are going to shoot it. Of course, when you arrive to the set and things start to take shape, you change your plan.”

What Levinson didn’t anticipate was how much Malcolm’s bitter rants about critics and showbiz at large seem like they could be his own. Malcolm spends a lot of time bemoaning a mostly favorable review by “the white girl from the Los Angeles Times,” and a quick Google search will tell you that a white woman from that very publication did not care for Levinson’s previous movie, the hyperviolent satire “Assassination Nation.” Whatever Levinson’s intentions, this aspect of “Malcolm & Marie” makes it navel-gazing, as many reviews have noted.

During a recent Zoom conversation, I asked Levinson whether he does, in fact, identify with Malcolm. After all, maybe he’s more of a Marie, lambasting Malcolm’s relentless self-involvement. Independent of those dynamics, the specifics of how “Malcolm & Marie” came together are pretty fascinating, too. (For reference, he refers to Zendaya as “Z” and Washington as “JD.”)

There’s a lot riding on this movie for a number of reasons, one of which being that Netflix paid a reported $30 million for it. That is a gargantuan sum for a film acquisition. Even the splashiest Sundance or TIFF premieres usually go for under $20 million. What were those conversations like, and how did you feel when you were hearing those numbers?

Look, I think the reality is, this started off as a very simple idea. Z said, “Sam, you think we can shoot a movie in my house?” “Euphoria” had been shut down for a period of time. Marcell and I started talking about what was possible. My wife, Ash, and our producers, Katia Washington and Harrison Kreiss, started looking into COVID protocols and how we can pull something off. Eventually, out of that came this idea of doing a movie in one location. And at the same time, it was a way of getting our “Euphoria” crew back to work because it was an uncertain time for everybody.

We were able to design a financial structure in which all of our department heads and staff had actual ownership in the movie. We were able to carve out a portion of the backend for [the nonprofit organization] Feeding America. If we were able to get back to work, we would be able to help provide for people who aren’t able to work at this particular moment in time. And also, just on a creative level, the challenge of telling a story given these restraints: just two actors, one house and, essentially, just one long scene. I think the expectations weren’t more than, “Can we do something that’s engaging?”

Was it filmed at Zendaya’s house? I didn’t realize that.

No, no, no. It wasn’t. That’s just the initial idea. She was like, “Can you come over here?” The main reason we couldn’t do it in Z’s house is because we couldn’t get a permit to shoot there. The only place we could get a permit was Carmel because it doesn’t require one for private property.

How did you arrive at the aesthetic of the film, specifically the black-and-white roving style in which you filmed these long conversations?

I think there was a couple of things that informed that. Early on, it was sort of an instinctual thing that Marcell and I both felt. And also, once the script started to take shape, I knew it was about this couple in a house, that it was about Hollywood, it was about storytelling. Marcell and I started to go through our references of images and different films. We’re looking at “La Notte,” Joseph Losey’s “The Servant,” “Bunny Lake Is Missing,” “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” And I think it was striking to us that all of these beautiful black-and-white films featured all white actors. By the time Black actors were getting opportunities in Hollywood, black-and-white films had fallen out of fashion.

Spike Lee has done it since, and Charles Burnett. But I felt that, because this was a film about Hollywood, because it was about the industry, it felt like an interesting way to reclaim the iconography of that era of filmmaking and frame these two actors in the timelessness of some of these indelible images.

In plotting all of that, how specifically did you map out the film? You have this incredibly wordy script and this large, rambling house where your two actors can theoretically move here, there and everywhere. Do you give them that freedom? Or is it all blocked out with precision?

So, we shot the first day. We had a very formal idea as to how we were going to shoot it: dolly shots, very clean Otto Preminger-style choreography. We shot the whole day. Marcell and I get into the car. We both felt like it was too clean. There wasn’t enough life. It looked like a fucking whiskey commercial or something. So we go to sleep, we’re depressed. We wake up. Marcell says, “What if we would just do handheld [cameras]?”

We were watching “Bullet Ballet” on our phones on the car ride up to set. We get to set. I tell JD and Z, “All right, we’re going to throw out everything we did yesterday. We’re going to start over.” JD goes, “You mean there’s nothing usable?” I go, “No. No, nothing. We’re going to throw the whole thing out.” He’s like, “OK. We did like 30 takes though!” I’m like, “I know. Throwing it out.”

I think the reality is that people tend to assume that because I’m a filmmaker and Malcolm’s a filmmaker, that I am 100% Malcolm. I completely reject that idea.

Sam Levinson

So then we did the whole thing handheld. We got into the car towards the end of the day, and Marcell’s lost 10 pounds. He’s sweating. We both look at each other, and we know that there’s no design to the movie, that it feels too haphazard. So we just decided to jump forward and move ahead. And we were doing a connecting shot from the bathroom to when JD comes in [at the beginning of the movie]. He’s listening to James Brown in the living room, and we just decided to play the whole thing out in a seven-minute take so we’re entering the movie from an objective standpoint. We’re able to see the world of the film. We’re able to see John David, or Malcolm, totally excited, celebrating. He’s in one universe, and Marie’s in this other universe, smoking a cigarette, not having the best night of her life. And I think it was important because of the nature of the film, which is essentially this Socratic dialogue between these two characters. Someone stakes a position, the other person starts to pull apart the threads, and it just continues to go on and on like that.

I think the reason that that shot worked and helped frame the film is that it instills a certain kind of confidence that we’re not coming into this taking sides. This is an ongoing battle between these two characters and a fight for acknowledgment and a mining of the truth of their relationship and the imbalances of power. That’s why it worked, and that’s why it felt right. After that moment, Marcell and I realized that we had to table any ideas that we had previously had about how we were going to shoot it and be humble to the life that was taking place on set, and to make sure that we weren’t approaching it from too subjective an angle.

That makes a lot of sense. You mentioned knowing from the outset that the DNA of the movie was about Hollywood. Aside from the fact that you yourself are a filmmaker and a movie lover and therefore very invested in that world, why was that the choice you made? I wonder whether you considered other professions, something perhaps a bit more universal?

What do you mean by universal? What’s a more universal profession?

Almost anything. I mean, to be fair, movies about movies are not inherently relatable to the average person, however entertaining and effective they may be.

I feel like this is that age-old thing. You know, you watch shows about doctors. I don’t understand what they’re talking about when they’re saying, “We need 10 CC’s of this!” You know what I mean? You watch a show about lawyers. I don’t understand the life of a lawyer. If I were to watch a show about, you know, someone who’s building a fence, I don’t know much about building a fence. I think movies by nature are a window into a world. I don’t necessarily place a particular value on the relatability of the world because I think it’s the film’s job to either make you care about the characters or not. And if you don’t, you don’t.

So, I don’t think that there was ever any consideration in that, because I sort of reject that idea in general. But I do think that what was interesting about him being a filmmaker is it allowed the argument to not just be the argument, right? It’s not just, “You did this to me, I did that to you.” It’s because he made a movie and interpreted her life and subsequently didn’t give her credit for it. It gives us another way to explore and examine that relationship through the lens of something that’s fictional and up for interpretation, which gives it a whole other kind of multifaceted side to the exploration of their relationship.

As both the writer and director, how much of Malcolm’s perspective and experiences did you relate to, and how much of Marie’s perspective and experiences did you relate to? People are going to come away from this movie wondering whether Malcolm’s rants about critics are really just Sam Levinson’s rants about critics.

Right. But Marie sides with the critic.

Yes, right. That’s why I ask where that ratio was for you.

Right, but this is what’s so funny about this whole conversation. What was interesting to me is, Malcolm receives an incredible fucking review, a great review. There’s a ton of praise, but it’s not in the exact way he wants it to be. So therefore it completely unmoors him as a character until he’s screaming about identity and [physicist Bruno] Pontecorvo at the fucking trees. It’s a way, I think, to explore how truly sensitive and completely narcissistic and absurd this character is in this particular moment.

To further compound that, we then have Marie, who’s saying, “You know, not only do I agree with the critic’s criticism in that one small part, but I actually am going to take it a step further and say that her problem with you as a filmmaker is my problem with you as a human being and a partner.” I think it gets to the key theme of what this movie is about, which is if we are not able to listen to critique, we are not able to grow as artists — and, more importantly, as human beings.

What I’ve been a bit surprised about is I feel like the way certain people are interpreting this movie. They’re mirroring essentially what Malcolm does to Marie, which is to completely negate and dismiss her narrative in this movie by just getting hung up on what he’s saying. Her counterargument, which I might argue is the emotional, gravitational pull of the entire film, is going unnoticed because someone got their feathers ruffled.

Do you think there is any credence to the idea that this movie is, at least in some regard, a response to reviews that you yourself have received? Specifically, perhaps, from the Los Angeles Times, with “Assassination Nation”?

No. A lot of people didn’t like “Assassination Nation.” That’s a totally valid position for one to hold. Again, Malcolm gets a phenomenal review with one piece of criticism that Marie agrees with and takes a step further. I think that there’s a strange irony to it. And in a way, the response is in some ways mirroring the film. What’s interesting is that I think it is this sort of Socratic dialogue between these two characters. The film doesn’t take a position on “these are the right ideas, these are the wrong ideas.” They’re just ideas. They’re just discussing them.

But I think that that’s maybe unusual right now, just culturally speaking, that you allow the audience to decide what they agree with or disagree with. I think that there is no ideological throughline that people can say, “Oh, OK, it’s saying exactly X, Y, and Z.” I think the reality is that people tend to assume that because I’m a filmmaker and Malcolm’s a filmmaker, that I am 100% Malcolm. I completely reject that idea.

That’s why I asked about the ratio between the Malcolm and the Marie in you. You’re not necessarily just Malcolm.

But Marie is, in some ways, an extension of [Zendaya’s “Euphoria” character] Rue. I think I’ve been very honest and forthright about how much of myself is in the character of Rue. I am someone who is a recovering addict. There is an enormous amount of myself in Marie. And I think that what’s happening here is these two characters are reflecting different aspects of not just myself, but also the people I’m writing the characters for and that I’m collaborating with on the characters.

This isn’t a script that was written in isolation. This is a script that I wrote where every day I called the actors, read it aloud to them, discussed it for hours on end, had 65 pages of a script, got to Carmel, sat down with Marcell, Z and JD, and talked out every single aspect of this movie. They’re not just actors — they’re producers and co-financiers of the movie.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source