Often it’s almost impossible to have a real conversation about a venerable figure amid today’s stan culture — and even sometimes frustratingly discouraged. That’s especially true when it comes to older Black icons who paved the way for those who came after them, and whose less comfortable truths are often pushed aside out of respect.

But director Reginald Hudlin’s “Sidney,” which explores the life and career of the late Sidney Poitier, actually has those conversations. It does so unflinchingly and candidly. And it includes a variety of equally respected heroes of Black cinema who are compelled to reckon with the full portrait of Poitier, a man who both aspired and inspired just as much as he frustrated and disappointed.

We rarely ever really talk about that last part. “Sidney” implores us anyway.

It’s a funny thing too, because for many of us when it was announced that there would be a documentary on Poitier, a few questions immediately sprang to mind: Will it include his affair with “Porgy and Bess” co-star Diahann Carroll, who, like him, was married at the time?

Will it confront the Uncle Tom dialogue that rose during the blaxploitation era that was far less compromising about how Blackness was portrayed on screen? The answer to both these questions is yes and thankfully so.

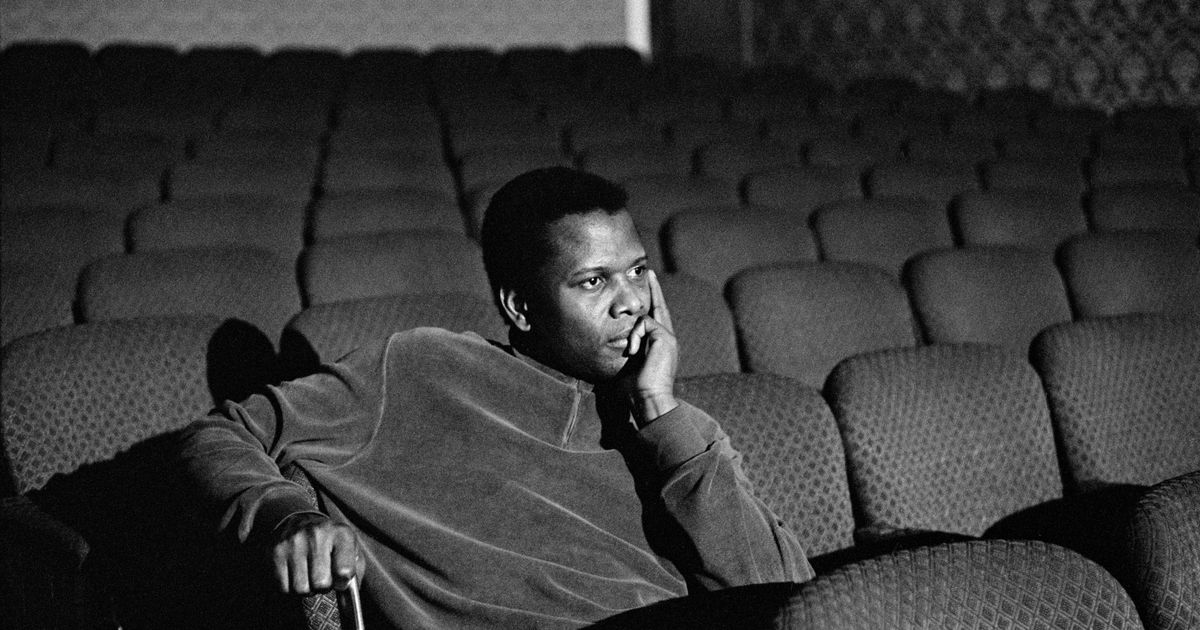

Photo by Film Publicity Archive/United Archives via Getty Images

It’s not about sensationalizing or tarnishing the reputation of a man who burst open the doors of opportunity for Black people in Hollywood and encouraged his contemporaries to advocate for civil rights with figures like Martin Luther King Jr. Rather, it’s about honoring his humanity — every facet of it.

Hudlin is more than equipped for the job. After all, he jumpstarted his career on the heels of Poitier, who intentionally went behind the camera to direct movies by and for Black folks like “A Piece of the Action,” “Let’s Do It Again” and “Uptown Saturday Night” in the ’70s.

Known for helming Black classics like “Boomerang” and “House Party” in the ’90s, Hudlin is likely familiar with the quiet expectation to compromise in a system that usually only celebrates you when you play by its rules.

Hudlin also has the benefit of retrospection when telling the story of “Sidney.” He’s got 30 years in the game and has relevant insight into the system of Hollywood today. But he also understands with compassion what it was like years prior for actors like Poitier.

That’s why so many passages throughout “Sidney” feel so honest and empathetic, while also interrogating and sobering. Hudlin certainly does more than his due diligence by amassing the full scope of Poitier’s life growing up poor in the Bahamas through interviews with the actor as well as archival footage of Poitier reflecting on his experiences.

Courtesy of Apple TV Plus

He ultimately pulled himself up by his bootstraps, moved to Harlem, and bet on his immense talent. There he faced and, in a sense, overcame a whole new set of challenges as a young Black thespian in relentlessly white spaces.

While Poitier earned his stripes from performing in Black spaces like the American Negro Theatre, it wasn’t until white Hollywood took notice that he became immortalized. That’s a fact that catalyzes a lingering question in “Sidney” of where in the zeitgeist Black actors belong once they receive white adoration.

You don’t find an answer in interviews with some of Poitier’s white contemporaries. Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford in the film unequivocally admire him for who he was and for whom he tried to be. But you might be able to come up with your own answer to that by watching some of the clips Hudlin excavates in the film.

Poitier is interviewed by a white male journalist in one scene of archival footage— always a white journalist back then — just when his career is taking off about how he got his start. The interviewer brings up the fact that Poitier was asked to get rid of his “bad native accent was “bad” to get more work. And how did the actor remedy it? He revealed to the interviewer he taught himself by imitating a white guy he saw on screen.

It’s a brief exchange between two men that probably wouldn’t have struck anyone back then because it was expected. But looking back on it now within the story of “Sidney,” it says a lot about the landscape through which Poitier earned his success — and how he even, perhaps subconsciously, sometimes upheld it.

Photo by Gilbert TOURTE/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

“Sidney” also finds Poitier’s descendants, those who might honor him the most like Halle Berry, Oprah Winfrey, Morgan Freeman, and Spike Lee, wrangling with the complexities of his career while also venerating him. Because, as we too often forget, both things can be done at once.

Harry Belafonte, one of Poitier’s longest friends, who often joined forces with him in the fight for racial justice, doesn’t mince words when talking about their playful professional rivalry (Poitier’s career blew up on the night he stepped in as an understudy on stage for Belafonte).

The two often were up for the same roles but, even more crucially, they disagreed on several political issues that sometimes resulted in them not speaking to each other for years at a time. Belafonte is also open about turning down Poitier’s role in “The Defiant Ones,” because his character, an escaped convict, helps his white, racist fellow convict (Tony Curtis).

In response, Denzel Washington points out something that is not often unacknowledged in these kinds of conversations: opportunity. While Poitier stood up for a lot of things and was very outspoken about issues of racism and other injustices in and beyond Hollywood, he was also a married father of two with financial obligations.

Not everyone, as Washington says, has multiple forms of income to bring home. While Poitier was hustling in Hollywood, Belafonte was also making money on stage, “Dayo-ing.”

Photo by Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images

But Poitier was well aware of these conversations about him and his film choices. He still stood behind his decisions, while also recognizing the points people made about them. His earnest response was to start a Black production company in the ’70s.

But when, how and whether to confront the role of the Black image on the screen — especially during his time — was trickier to maneuver.

The question of compromise could be asked of any of the Black luminaries Hudlin spoke to in “Sidney” — and for what it’s worth, they’ve all confronted questions about navigating whiteness in Hollywood. Winfrey even openly acknowledged how some Black audiences turned against her for what they saw as catering to white audiences on her hit, self-titled TV show.

It’s what helped bond the two figures. There’s a moment when we see a visibly emotional Winfrey, who like Hudlin is a producer of “Sidney,” dissolve into tears over her love for Poitier as the camera fixates on her for several seconds.

What’s most clear at this moment, though, is how these questions of how Blackness shows up, and for whom, in largely white spaces remain as relevant today as ever. There’s even something to be said about the fact that Poitier was a Black sex symbol, propped up and adored by many Black women, yet he left both his first wife and, ultimately, Carroll to marry a white woman.

Photo by Earl Leaf/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“Sidney,” bafflingly, doesn’t even acknowledge this aspect of his personal and romantic life. In a film that explores every other complicated subject around Poitier and the world in which he thrived, this omission by Hudlin and screenwriter Jesse James Miller seems odd.

It’s especially peculiar when you think about it in terms of the long history of Black men choosing white romantic partners after gaining success in white spaces.

There’s certainly no question of whether Poitier loved his widow Joanna Shimkus. Both she and their children, as well as Poitier’s children with first wife Juanita Hardy, are all interviewed in the film and speak highly of his relationship with each of them (with respect to the fact that Poitier cheated on Hardy with Carroll, which understandably devastated her).

They say he also encouraged his children to have relationships with each other, and his biracial kids to understand their identities. Still, that’s the one area of the film that doesn’t feel complete.

But when “Sidney” soars, which is most of the time, it is an absolutely satisfying portrait of a man who gave us so much within the confines of a system that was making up new rules for his unprecedented success as he went along, and the complex ways in which he responded to that.

“Sidney” doesn’t bother to simplify details around Poitier’s biography, nor does it try to complicate his story. Rather, it honors the very real complexities of the life he lived.

“Sidney” premiered at the 2022 Toronto International Film Festival, and will be released on Apple TV Plus on Sept. 23.