[ad_1]

Writing a list of the best books of the year is always a bit of a fool’s errand; for a single person to read all of the contenders, with due care, is nearly impossible, and then there are the confounding factors of taste and bias and simply having an off day. That’s in a normal year.

For many of us, 2020 rearranged our relationship to reading. Perhaps there were vast new stretches of unfilled time, and to-read piles offered themselves as a solution. Perhaps uncontrolled anxiety and the lure of Twitter made concentrating on the page more daunting than ever. Perhaps extra shifts needed to be picked up at work, or financial stresses consumed every waking moment.

In my home, there was a baby to keep us busy. It would be fair, I think, to say that my reading and other cultural consumption habits were obliterated by pandemic parenting. Every day I’d gaze wistfully at my to-read stacks, but when I’d snatch 15 minutes to open a long-anticipated novel, the words would swirl in front of my bleary eyes. I know there were books I read that tumbled into the foggy chasms of my mind during maternity leave and books that sat ignored on my nightstand while I sorted tiny socks.

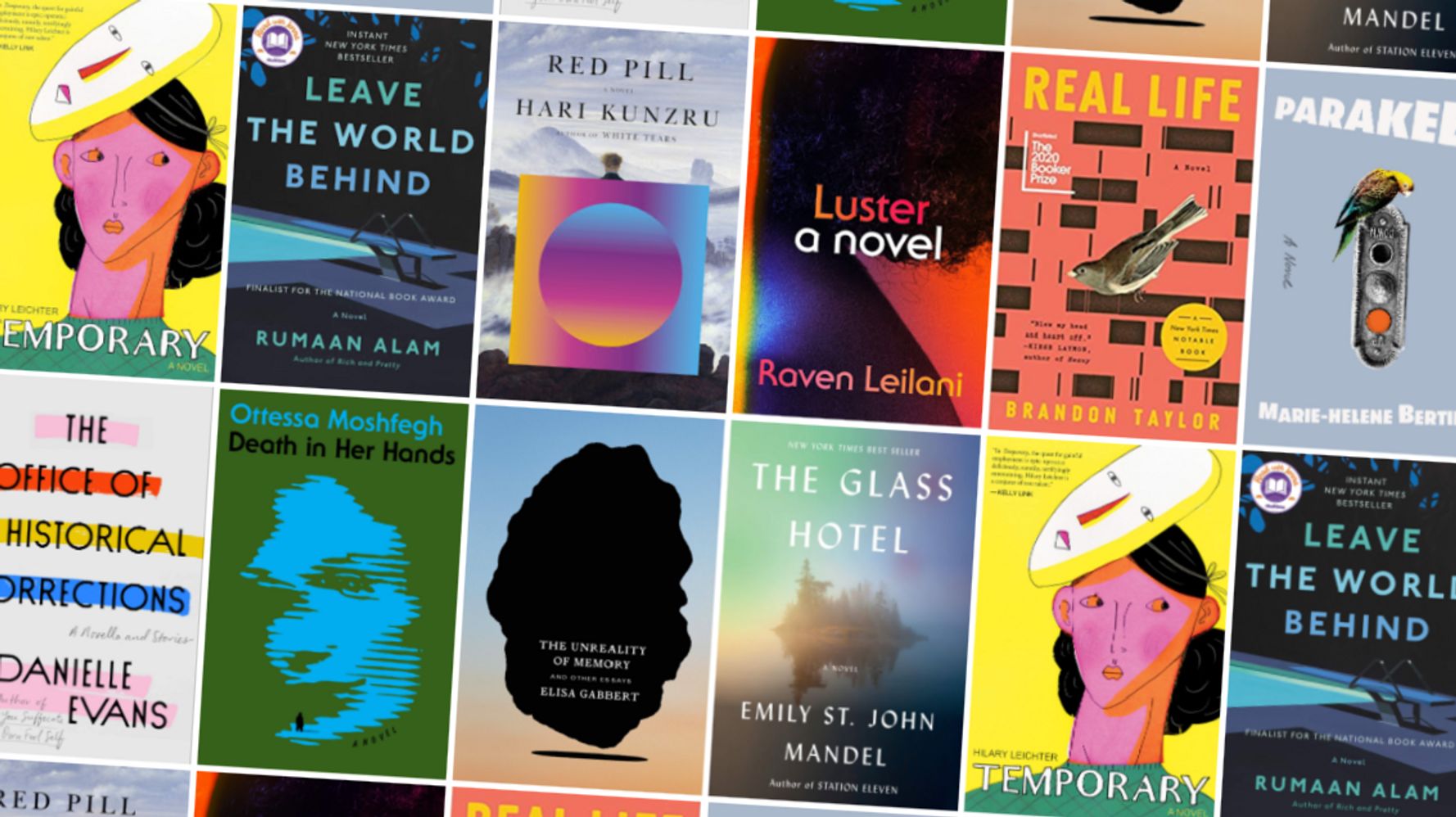

But at the end of a long, monotonously miserable year, I also want to celebrate the books that shook me awake. Here are my favorite 10 books of 2020:

“Temporary” by Hilary Leichter

Instead of a job, the young woman at the heart of “Temporary” has a perpetual stream of temp gigs: door opener, chairman of the board, pirate. Instead of a boyfriend, she has boyfriend fragments: a handy boyfriend, a culinary boyfriend, a tallest boyfriend. Instead of a life, she has the dream of one, the stable existence she knows would be hers if she ever became a permanent employee. Her mother coaches the young woman like a workplace mentor and disapproves of her special affection for one of her boyfriends: a temporary worker can’t afford any permanent distractions. The novel’s episodic form and deadpan blend of surrealism and corporate euphemism allow for a funny, tender exploration of how our job and employment status encroaches on other parts of our life and identities. Leichter plays lightly with language and metaphor, building a world that gives concrete form to the economic and social precarity that shapes so many people’s lives today.

“Real Life” by Brandon Taylor

Taylor’s debut is of a rare and vital sort: It examines the social relations that govern how we mostly interact with each other while also ripping off the polite filter to expose the seething emotions underneath. Wallace, a quiet biochemistry grad student at a Midwestern university, has recently lost his father, with whom he had a difficult relationship. At the lab, someone has sabotaged his latest batch of nematodes. With his mostly white friends, well-meaning but often careless, he’s guarded. As the novel unfolds, Wallace finds himself entangled in an unexpected romance with a straight friend while the situation at the lab, despite his determination not to make waves, spirals. Taylor’s grip on the subtle movements of the human heart and psyche is masterful, as is his prose; every word in “Real Life” feels intentional and every sentence perfectly calibrated.

“The Unreality of Memory” by Elisa Gabbert

Gabbert’s essay collection, a ramble through the scary, the uncanny and the unsettling, made an ideal companion reading to 2020. In essays about disaster and disaster movies, the fear of massive objects, the Trump presidency, the slipperiness of memory and the present moment, and more, the poet and critic opens up side doors, windows and trapdoors in the way we think about each topic. Reading her thoughts on slow disasters like climate change or eerily relevant ones like pandemics often left me shaken, but with a newly enriched understanding of how we, as humans, experience crisis and make sense of our fragile lives.

“The Glass Hotel” by Emily St. John Mandel

This year, I finally read Mandel’s breakout hit, “Station Eleven,” set in the aftermath of a devastating pandemic — and her new novel, which is no less dazzling. Vincent, a troubled girl from a tiny town on Vancouver Island, grows up to work in the opulent Hotel Caiette nearby, where she meets a wealthy investor. Years later, while working as a chef on a ship, she tumbles overboard. Her life in between is chameleonic, difficult to trace. Mandel’s characters, and the worlds they occupy, are cool and remote, demanding and rewarding close attention. Economic catastrophe is Mandel’s central subject in “The Glass Hotel,” which revolves around a Ponzi scheme and the financial crash of 2008, but the novel is a prismatic depiction of public crisis and private pain, moral luck and collective culpability, and the ripple effects of suffering.

Perhaps the least romantic novel about a bride I’ve ever read, “Parakeet” takes place in the week before the protagonist’s wedding. As she attempts, at her fiancé’s request, to get into a better mental state before the big day, she’s visited by her late grandmother in the form of a parakeet. Her parakeet grandmother has a request of her own: that she reconnect with her brother, a playwright currently staging a work based on the bride’s past traumas. The ghostly parakeet is just the first fantastical element in a dreamlike quest for familial connection and healing. By turns goofily funny and agonizingly raw, Bertino’s bewitchingly chaotic novel captures the senses of dislocation and fragmentation that can accompany profound suffering, and the urgent search for stability in the wake of trauma.

“Death in Her Hands” by Ottessa Moshfegh

Moshfegh’s latest lacks the smooth assuredness of her breakout works “Eileen” and “My Year of Rest and Relaxation.” But this sometimes wobbly, palpably anxious novel is one of the books that has stuck with me most since reading it this spring. Vesta Gul, an elderly widow, discovers a note in the woods near her house while walking her dog. “Her name was Magda,” it reads. “Nobody will ever know who killed her. It wasn’t me. Here is her dead body.” There’s no body (so, one would think, no crime), but Vesta quickly becomes convinced that the slaying is real ― and consumed by her hunt for the killer. A sort of meta murder mystery, “Death in Her Hands” evolves into a searching portrait of grief, loneliness and the comforts of storytelling.

“Luster” by Raven Leilani

Several of the best books I read this year were about young people eking out precarious or marginal lives for themselves, and of these, “Luster” is the most immersed in the demoralizing details of financial desperation and social isolation. Edie, who works as a managing editorial coordinator at a children’s imprint and harbors unfulfilled artistic aspirations, is young, frustrated and underpaid. She has flings at the office, which end up backfiring on her; she gets involved with an older, married white man in a fraught open relationship with his wife. Somehow she becomes deeply enmeshed in the couple’s life only to realize that the other woman wants her to help them parent their adopted adolescent daughter, who, like Edie, is Black. Though her voice is disaffected, even cynical, Edie’s sensitivity is acute. She turns to food delivery apps to make money after losing her job, accepts the offer of a guest room at her lover’s Jersey home and tries to keep her expectations low, but her yearning to be truly seen leaps off the page — a yearning that is continually met with the realization those around her, when they see her, see her mostly as a means to an end.

As wake-ups go, Alam’s apocalyptic vacation novel is akin to sitting bolt upright in the middle of the night, convinced that something is terribly awry. An upper-middle-class white family heads out to a rental mansion on Long Island for a getaway, where they watch TV and gorge on ice cream and hamburgers. The vacation has barely begun when an elderly Black couple shows up at the door, saying they’re the owners of the house and that they’ve fled from New York City after a mysterious event. The two families, isolated together in a summer idyll, receive more and more disturbing hints that a catastrophe has befallen the region, if not the world, but see no path forward but to continue relaxing by the pool and making indulgent meals. It’s a harrowing story of modern life, in which the consumerist excesses of the American elite are juxtaposed, to chilling effect, against the existential threats to human life as we know it.

“Red Pill” by Hari Kunzru

The narrator of “Red Pill,” a happily married writer working on a vaguely conceived book about lyric poetry, is having a midlife crisis. Unable to finish his new book, he applies to a residency at the Deuter Center, an institute near Berlin. Once there, he discovers a catch: The center turns out to be a panopticon, where all the visiting scholars have their keystrokes logged and work in glass offices so that their productivity can be tracked. Plagued by his own anxieties and paranoid of his surroundings, he spends his time watching a graphically violent cop show and beginning to decipher what he believes are hidden messages from the show’s writer. The boundaries between reality and his own troubled fantasies become blurred until he feels he must take action. Though the denouement feels a bit pat, Kunzru’s portrait of a man and a world in crisis thrums with tension, viscerally evoking the real and imagined horrors that can seep through the cracks to threaten the tidy lives we construct for ourselves.

“The Office of Historical Corrections” by Danielle Evans

Evans is a writer with a gift for the sudden knife in the ribs. Her stories start out calm, almost matter-of-fact. The women she writes about seem to examine the situations they find themselves in with some detachment, though with varying degrees of insight. The scenarios range from the slyly funny to the poignant: In one, a photojournalist at a male friend’s wedding tries to make nice with his suspicious bride; in another, a white college student becomes the focus of a firestorm on campus after a picture of her in a Confederate flag bikini is posted on social media; in a third, a young woman finds a toddler abandoned on a bus and begins to care for him like a mother. When I least expected it, Evans would deliver a brutal twist, a new revelation of the wounds people live with. There’s always something buried beneath the surface, something broken or sinister or simply embarrassing. I hurtled through these stories and ended each one gasping back tears.

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source